Check Out Faster and Keep Your Dollars

When you purchase food at the Middlebury Natural Foods Co-op (MNFC), you support the hundreds of local producers who live in our area, and you are keeping the money in local circulation. And, as a member-owner, you own shares in this store and will receive an annual patronage refund based on your purchase history! The shares you hold represent your whole-hearted commitment to community-produced and distributed healthy foods.

Did you know you can increase another aspect of “keeping it local” by simply adjusting how you pay at checkout? In past articles I’ve written to make folks aware of this topic, I noted that MNFC paid more than $100,000, then $150,000, and then the number was close to $200,000 in annual credit card fees! The fees have been increasing each year. Last year in 2020, we paid $272,161 in credit card fees! Consider that this startling amount of money is extracted from our local community and flows to out-of-state banks. Think about what could be done locally with these funds, either through increased community supports, or improvements in customer services. While I certainly do not want to “guilt” anyone for using a credit card, there are options to consider for avoiding those fees. The use of checks or cash is one possibility, but this is not always convenient.

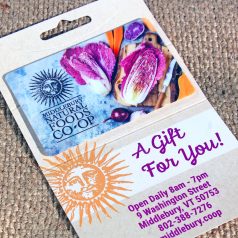

The easiest way to avoid the fees and using up checks or having cash on hand is to use an MNFC Gift Card for all of your Co-op purchases. This card can be obtained from any cashier, and you decide how much money you want on the card. Simply write a check for that amount, then use the gift card every time you shop. The card acts like a credit card with your money on it, but there are no fees. It is another form of “cash” and thus should be kept in a secure place. There is a number associated with each card that can be found on the back. I keep a photo of the id number of my card on my phone so it is always handy and secure. If you lose the card, the card can be deactivated if you have the number, and a cashier can look up your balance and apply it to a new card. The gift card works just like a credit card or check or cash and is linked to your coop account. The balance of the card shows up at the bottom of each receipt every time you make a purchase so you can keep track. When the balance runs low, simply write another check or use cash to load the same card with more money! I tend to reload each month, and it keeps me on my food budget! I remind you that writing a check or using cash to add money to the card is the way to go; if you use a debit or credit card, it defeats the purpose.

There are several advantages to this process:

- You can budget what you believe is reasonable for you to spend at the Co-op, say for a month’s time, and keep track of your spending.

- Going through the checkout line is extremely quick and efficient. The cashier scans your card, you get a receipt, and you’re done! Nothing to sign, no check to write, no numbers to punch in, no waiting for change. The cashiers like the ease of this process and you’re apt to get some unsolicited positive regard from them.

- During the surge of COVID, using the gift card minimizes contact involved with using common pens, dealing with the credit card terminal, and handling cash.

- Finally, remember that an MNFC gift card is a wonderful way to give anyone a present, for any occasion. An MNFC gift card can encourage someone new to the Co-op to make their first visit and can introduce long time customers to this very efficient way of paying for purchases.

- Most importantly, using a Coop gift card this way eliminates the credit and debit card fees the Co-op has to pay to banks and financial. Don’t forget, debit cards have fees as well!

Once you try it, you’ll wonder why you have not done this all along. It is such a quick and convenient way to pay for your groceries, and keep your dollars local – it is truly a win-win. This is how I have paid for my MNFC shopping for the last five years, and I intend to for the next five years and more! It’s a great intention to set for the rest of 2021, I encourage you to give it a go! I think you’ll love it!

Louise Vojtisek is a Middlebury Natural Foods Co-op Board Member