Our Food Waste Practices – Keeping Up with Our Ends and Meeting the New Law

As my hero Jim Henson anthropomorphized through his alter ego Kermit, “It’s not easy being green.” That is unless you are the Co-op with a staff, management team and board who aim to be “green” every day. This means having systems and practices in place that nourish and protect our bodies and the earth. Not an easy thing to do when you are a business that deals in perishables and foods with shelf lives. I was fortunate to work with 16 Middlebury College seniors this past fall in the Environmental Studies Community-Engaged Practicum (ES401). We studied Climate Change and Solid Waste in Vermont and beyond by evaluating the goals and impacts of implementing Vermont’s Universal Recycling Law (ACT 148). Much of this article borrows from the research these students conducted.

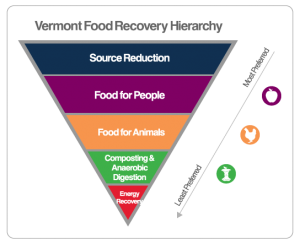

Act 148 was passed in 2012 to increase diversion rates of solid waste into recycling programs keeping recyclables and organic materials out of landfills. Aside from being difficult to site, landfills are also some of the largest sources of greenhouse gases. The law requires that Vermonters divert all compost and recycling from landfills. The law prioritizes alternative food waste options, encouraging donation, composting, feeding livestock and converting to energy with the goal of re-conceptualizing how we manage and think about food waste – it as a resource, not waste. The restructuring of the waste system through Act 148 is being implemented in stages. Initially, the law applied only to large producers of waste, but smaller producers are being phased in year by year, requiring proper sorting of trash, recyclables, and compostables down to the household level.

Our Co-op will need to be in compliance with Act 148 by July 2020. As I looked into how we are preparing for this new law, it turns out we are way ahead of the game. You see, in 2017 we donated perfectly good food (12,619 pounds to be precise) that we could not sell to the Champlain Valley Office of Economic Opportunity (CVOEO). And, that is not all – food that cannot be donated goes to compost. This compost is primarily picked up by area pig and poultry farmers, but we also have Casella check once a week for any remaining compost unclaimed by farmers. We generate approximately 82,125 lbs/year of post-consumer scraps as compost which come mostly from the Produce department, the deli kitchen, some from Bulk, and also from the compost bin near the cafe where customers deposit their lunch scraps. All recyclables and food scraps produced and disposed of by the Co-op are already being properly sorted and leave our site free of cross-contamination between trash, recycling, and food scraps.

On a larger scale, the diversion of food scraps from landfills is important in reducing the methane emissions produced by Vermont. The environmental impact of food waste is of a high magnitude; “if global food waste was a country, its carbon footprint would rank third, behind only China and the U.S.” (Food and Agriculture Organization, 2013). Greenhouse gas emissions resulting from the decomposition of organic wastes such as food scraps in landfills are a contributing factor to climate change. In landfills, the decomposition of food, the single largest component of municipal solid waste reaching our landfills in the United States, accounts for 23% of all methane production in the country (Gunders, 2012). The anaerobic decomposition that happens when organic materials are placed into landfills produces the methane, a greenhouse gas with an effect approximately 25 times stronger than carbon dioxide (CalRecycle, 2013). Their organic nature and high moisture content cause food scraps to decompose faster than other material in the landfills. As a result of the rapid decomposition, the methane is often released before landfills are capped, directly releasing it into the atmosphere without any opportunity for capture (Gunders, 2012). Diverting the materials that are a primary source of methane production would work to reduce the harmful environmental effects of the landfills.

Perhaps Kermit (aka Jim Henson) didn’t quite have it right – we can look to the leadership of the Co-op and say it can be “easy being green.”

Please note the primary source for much of this article appears in: “Middlebury Union High School Food Waste Recovery Initiative Final Report.” Middlebury College Environmental Studies Program, ENVS0401B, Fall 2017.

Nadine Barnicle is a Middlebury Natural Foods Co-op Board Member