Talking Trash with Kathy and Gwen, Part 2

The topic of waste reduction is common fodder at the Co-op – after all, one of our Ends (the reasons we exist as a cooperative) is to promote environmentally sustainable and energy efficient practices. It’s something we’re always working on and there’s always room for improvement. With this in mind, interested staff members at the Co-op began meeting monthly to discuss ways that our Co-op could improve our practices to move closer to a zero-waste operation. We realized during these gatherings that we have a lot of collective passion on the topic and many of us come from backgrounds that help inform the ideas we bring to these meetings.

Take Gwen Lyons, for example. You might know Gwen as a cashier at the Co-op, but you may not know that she holds a degree in Environmental Studies from UVM and her previous job was with the Central Vermont Waste District. She’s a glorified, self-proclaimed Trash Nerd. And she’s got a lot to share with us about what happens (or doesn’t happen) to items when we dispose of them. We wanted to share some of this with our Co-op community so we asked Kathy Comstock, who you may also recognize as a cashier, to interview Gwen. We’ll be sharing the interview with you in two parts. If you missed part one, click here! Read on for part two:

Kathy: So, what is Zero Waste? A quick Wikipedia search tells me that Zero Waste is “a philosophy that encourages the redesign of resource life cycles so that all products are reused. The goal is for no trash to be sent to landfills or incinerators. The process recommended is one similar to the way that resources are reused in nature.” And, so, it means that Zero Waste is especially important to consider now because we are running out of space and ways to handle our waste, correct? You told me in an earlier conversation that our landfills here in Vermont are almost at full capacity. And most of us, by now, have heard about China and other countries that are beginning to say “NO” to the US and not take any more of our recyclables.

Gwen: Right. Vermont only has one working landfill left in Coventry, Vermont – up near the Canadian border. Back when I was still working at CVSWMD, it was forecasted that the landfill only had the capacity for 20 years of waste remaining. So, what happens when the landfill is full? Not only is the permitting process for siting a landfill arduous and building one is very expensive, but any town in Vermont has the right to say “No” if they don’t want one. The big issue is that we (Vermont consumers) are happy to produce the waste, but don’t want to take responsibility for it when we are finished with something. Adding to the frustration is the fact that about 1/3 of what is being thrown away is organic material – food waste and yard debris, which will never break down in the anaerobic (or non-oxygenated) environment of a landfill. And although it will eventually break down, in doing so it will release methane, a very toxic greenhouse gas. Companies who own and operate landfills will boast that they can harness the methane to use for electricity, but in most cases, the methane is burned off on site. If you have ever driven south on I-89 past the Middlesex exit at night, you will most likely see the flame on the southern side. What you are looking at is the, now closed, Moretown Landfill burning off its methane. (Note: They do also harness methane to convert into electricity, and I believe they sell that electricity to the grid).

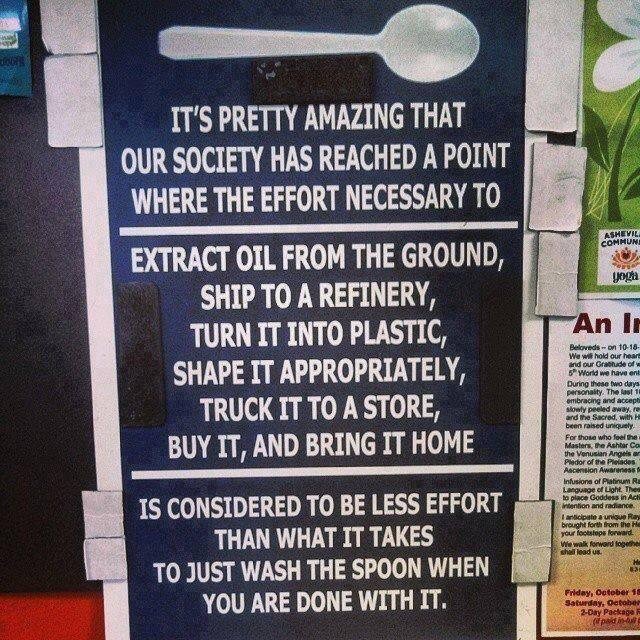

To further build upon your thoughts on zero waste, it’s not just the idea of sending nothing to the landfill or reusing things again. To me, zero waste is about not creating waste in the first place. A huge component of that is not buying products which come in packaging that has to be disposed of, in any sense. This means being a more thoughtful consumer – buying in bulk, not putting veggies in plastic bags, bringing your own reusable containers to the store, only buying to-go coffee if you have your own mug, etc. Truly living a zero-waste lifestyle, or as close to zero waste as possible, is do-able, it just takes planning and commitment.

But, I digress. Back to food scraps in the landfill. With the state’s Universal Recycling Law, by 2020 it will be illegal to put food scraps in the trash in Vermont. Although I think it is awesome and I am in complete support of it, we are again in the situation of having a forward-thinking idea, and creating the legislation to put it into effect, but are not necessarily prepared with the infrastructure to do it properly. Composting food scraps is easy on a small at-home scale. But being able to accept, process and compost an entire state’s worth of food scraps is not.

Kathy: But why is that so difficult?

Gwen: The long-short of it is two-fold:

The first challenge stems from the fact that start-up costs for creating a commercial composting facility aren’t cheap and there are complicated zoning regulations one needs to deal with, as well. Commercial composting facilities aren’t necessarily a money maker, especially compared to landfills. It’s a tough, dirty job and not everyone is interested in pursuing a career in compost. So, as a result, there are very few commercial composting operations in the state. While at the district I worked closely with Highfields Center for Compost in Hardwick, Vermont Compost Company in Montpelier and Grow Compost of Vermont in Moretown. The Chittenden Solid Waste District also runs a facility in Williston, which, from my understanding, is already taking twice the volume (of food scraps) the facility was designed to take in. And this is with only a small number of residents and restaurants participating in composting in that area. Obviously, we are going to need the infrastructure in place to accommodate those who can’t compost at home. One upside is that, while large-scale composting facilities can be expensive to build and operate, unlike in your household compost, they can compost oils, bones, meat, or dairy. This makes diverting food scraps from the landfill that much easier for VT residents.

The second challenge of composting on a large commercial scale is that, just like recycling, the stream needs to be clean. This means no contamination, including plasticware, PLU stickers, straws, stray napkins, plastic wrappers, etc. In regards to the position that I mentioned earlier as “Compost Monitor”, it was my job in a school with a new composting program to stand at the compost, recycling and trash bins at the end of lunch and help students sort what was left on their trays. When on field trips to Grow Compost of Vermont, one of the owners, Lisa, would always bring out her bucket of plasticware to show us what had been sifted out. And PLU stickers on apples, oranges, and bananas’? They are made out of plastic and will not break down. No one wants to find a PLU sticker in their garden, but it happens. Food scraps can be rejected if there is too much contamination, just like with contaminated recyclables.

As I mentioned before, maintaining a clean stream is critical for recycling. Loads of recycling can be rejected if the buyer determines there is too much contamination. So, as frustrating, and sometimes time-consuming as it is, plastics need to be rinsed clean of all food debris, and yes, this includes peanut butter. Honestly, I fill a container with water and leave it in the sink for the day. A good swipe and rinse with a scrub brush and it is good to go in the blue bin. Another tricky one is pizza boxes. Yes, your hot tasty pizza comes in what looks like an easily recyclable box, but if there is oil soaked into the cardboard it has to go in the trash. Why? The paper recycling process takes water – and water and oil don’t mix. A repeat offender is napkins, I see them in recycling bins all the time. They are not recyclable either because, as a napkin or tissue, the fibers in that material have already been broken down to their smallest size. There is no next step for them – into the trash they go. Of course, if you have a brown unbleached napkin it can most likely be composted – even at home. But, if you are sending your food scraps somewhere, check with them first. Those are just some common examples. (I can keep going if you want!) But one last thing, … just because it says “recyclable” on it, or has the iconic recycling symbol on it, only means it CAN be recycled. It doesn’t mean that it IS recyclable where you live.

Kathy: OK. So, this all sounds really overwhelming, but I don’t want to believe this is an impossible thing to overcome. I know we can all make some changes. I know that the Co-op has started to discuss and has already incorporated a few changes already. What kinds of things would you like to see happen at the Co-op?

Gwen: Our staff is working on creating new signage, which will be posted at the trash, recycling, and compost stations to help give clear guidance about what goes where. I know I mentioned it earlier, but it isn’t always easy, and although most of us have the best intentions, we could be accidentally putting something in the wrong place. And yes, after 5 years in the solid waste industry I have become a full-blown “trash nerd”. I’m sure people have seen me pulling items out of both the trash and recycling at the co-op, muttering to myself under my breath. Plain and simple, I have been rewired to care about trash.

And, there are definitely changes that we can all make to reduce waste when shopping at the Co-op. Some are easy, and others will take a little more planning and organizing. For instance, bringing in your own shopping bags is something that many of us already do, but there are still plenty of us who can adopt that practice. Also, thinking twice before using a plastic produce bag. Do your avocados or bananas really need to go into a plastic bag? Nope, they don’t. They naturally have their own packaging. Instead, bring your own produce bags … either reuse plastic bags from a previous purchase, buy reusable mesh produce bags or just put your produce items in the basket. Bring your own containers to fill in the bulk section. Only buy tea or coffee if you have your own mug. And, if you are choosing to eat at the co-op, choose a reusable bowl or plate instead of a to-go container. If you’re taking your food to-go, we have a new reusable take-out container, as well.

There are so many simple ways that we can change for the better, we just have to start retraining our minds to stop being okay with our current single-serve, convenience-based consumer practices, and take a moment to consider what re-using and recycling methods we can employ instead. The question I liked to pose to all the students I taught was, “When you throw something away in the trash, where is away?”

But what I really want to emphasize is the concept of zero waste. Before routinely buying, tossing, or consuming, consider if there is a way to avoid creating the waste in the first place. So much can be altered just by taking a moment to consider the options. No one is perfect, (not even me!). I, too, am guilty of going for convenience in a pinch. But, by taking the time to put reusable bags back in the car, grabbing a coffee mug “just in case” or choosing a plastic plate at the Co-op salad bar, and reframing our mindset, great strides can and will be made in improving our growing waste problems. Countries all over the world have demonstrated that collectively they can reduce waste, so we know it can be done. We just have to make the conscious commitment to lessen our footprint. And, with knowledge, I think we can.

Kathy: I think so, too. Thanks, Gwen!