Embracing Circularity

The latest report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the world’s official body for the assessment of climate change, spells it out quite clearly: humans are unequivocally increasing greenhouse gas emissions to record levels that are inconsistent with a future on this planet, AND we have the tools to turn it around if we act swiftly across all sectors. To keep warming within 2℃ above pre-industrial levels, global greenhouse gas emissions must decline by around 21% by 2030 and around 35% by 2035. The greatest opportunity for impact comes when we embrace systems change at the highest levels, and to embrace effective systems change, we must stop thinking linearly and start thinking in terms of circularity. So what exactly does that mean? What makes circularity different from sustainability? Isn’t circularity just recycling? How do we know if we’re succeeding? To take a deep dive into answering these important questions, we would love to share a guest blog post penned by Circularity Analyst Kori Goldberg. This post first appeared in the February 10th edition of the Green Biz Circularity Weekly Newsletter and has been shared with the author’s permission:

Question 1: How is circularity different from sustainability?

If you’ve ever taken a sustainability course, you likely have come across the following definition, from the 1987 United Nations Brundtland Commission: Sustainability is “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

Sustainability generally strives to reduce impacts on people and the planet as compared to the status quo — say a baseline of previous operations or the industry standard. The ambition for sustainability has grown since 1987, but in too many cases, sustainability is still seen as “doing less bad.” As Joel Makower puts it, “There’s little honor in ravaging the planet incrementally less.”

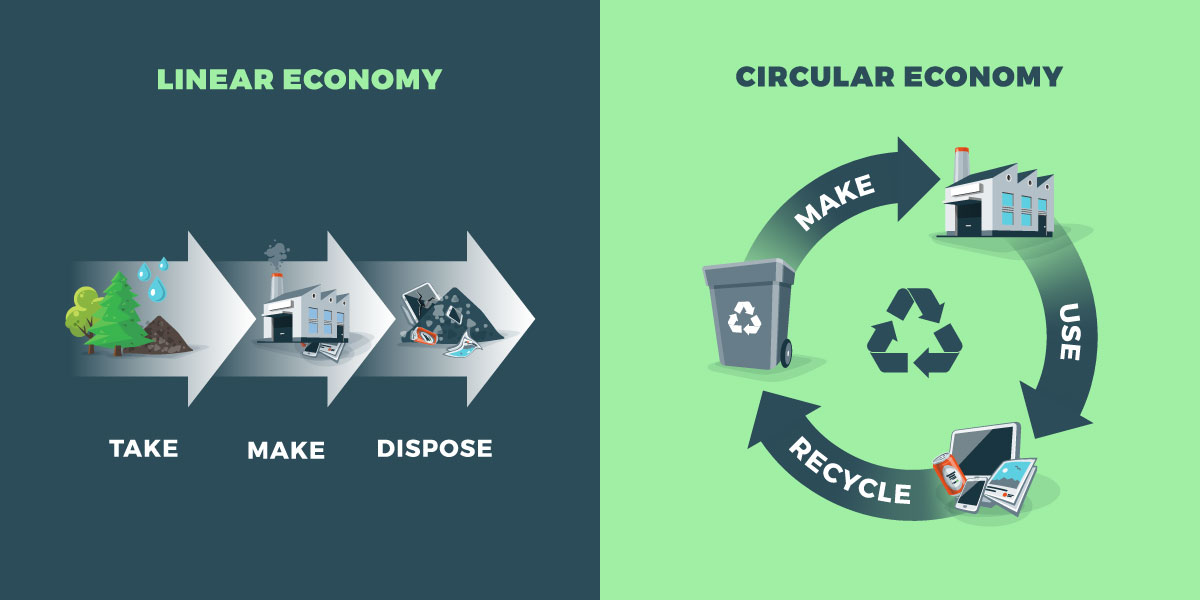

The circular economy is a systems approach that answers one “how” in our quest for sustainability. For simplicity, the circular economy is often described through a juxtaposition with the traditional “take-make-waste” system we are all familiar with, the linear economy. Unlike a linear system in which raw materials are extracted, transformed into products and then turned into waste with little regard to environmental, social and even economic externalities, a circular model aims to keep materials in the system at their highest value for as long as possible.

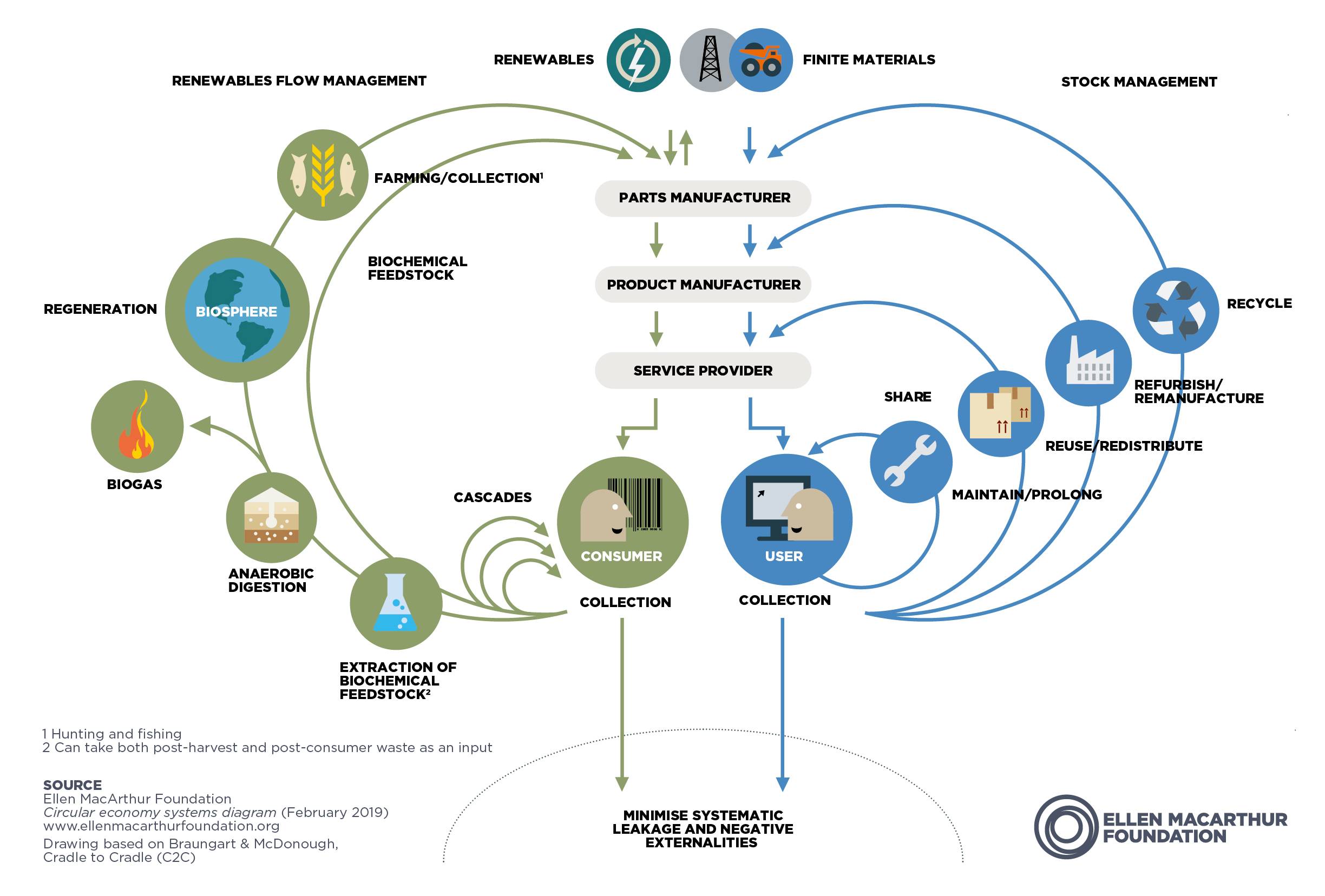

Sustainability is often considered an addition to an entity’s collective practices to improve the whole. Circularity, in contrast, must sit at the core of operations, aiming for profitability while simultaneously addressing global issues such as pollution, nature and biodiversity loss and climate change. Given the pervasiveness of linear economic models, circularity often requires a rebuilding of systems, business models and operations from the ground up. As a prominent thought leader in circularity, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation organizes the circular economy under three design-driven principles:

- Eliminate waste and pollution

- Circulate products and materials (at their highest value)

- Regenerate nature

The success of the circular economy at a systemic level depends on other global shifts: namely, the transition to renewable energy and a steady supply of responsibly sourced renewable material.

In summary: Circularity has a specific focus on the cycling of resources, lessening both our material use and waste to support a healthy planet. Sustainability deals in broader and more general efforts to reduce social, environmental and economic impact across an entity’s operations.

Question 2: Is circularity just recycling?

Given that circularity is all about keeping materials in use, at their highest value, for as long as possible, it’s natural to wonder if this just means recycling. And while this isn’t necessarily the wrong way to think about it, there’s some nuance here to be parsed out.

Circularity is, in fact, all about cycling materials repeatedly — so in this sense, recycling. This is in contrast to the way in which this term is more often used: to describe the industrial process of turning waste into new products. The latter type of recycling — for example, collecting plastic packaging and mechanically sorting, shredding, washing and reprocessing this plastic into new packaging — is actually one of the lower-priority strategies in the circular economy model.

Let’s back up a bit.

Integral to the circular economy are feedback loops, whereby products and materials are recirculated through the system. In nature, feedback loops nourish and add value to ecosystems. Take a tree that drops its leaves in the fall. These leaves decompose, feeding microbes and returning nutrients to the soil where they’ll be reabsorbed by another plant in search of nutrients.

In the biological cycle, renewable materials such as agricultural waste are recycled through the system through processes such as composting or anaerobic digestion. In the technical cycle, reuse, repair and recycling allow non-biodegradable materials to recirculate through the economy. This is demonstrated through the so-called “Butterfly Diagram,” seen below.

Designing our economic system with robust feedback loops to mimic nature is revolutionary; since the industrial revolution, we have built a system that forces nature to fit our economy rather than fitting our economy into nature.

Strategies such as increasing the durability of products, new business models that offer sharing, reusing, refurbishing and remanufacturing should be higher-priority strategies than recycling for many industries — from fashion to packaging to electronics.

There is a misconception that the circular economy is just a form of waste management or materials recovery. In reality, it is a model for a flourishing economy that minimizes waste as a natural byproduct of its inherent design of feedback loops that restore technical materials and regenerate biological materials.

Question 3: Degrowth and reduced consumption are tenets of the circular economy. How do we measure success?

As this is the hardest question to answer, I’ll respond with yet more questions. Is growth always good? Is growth the best thing to measure?

The success of global and regional economies have historically been measured by one single indicator, gross domestic product (GDP). But if current and future generations are to thrive within planetary boundaries, we must reimagine how we define progress and opportunity. This is the underlying rationale for the development of “doughnut economics,” a visual model for sustainable growth.

The model resembles a doughnut where the doughnut ring itself represents a safe and just space for humans to exist within. Inside the ring (the doughnut hole) represents a situation in which people lack essential social necessities such as healthcare, education and political voice. Meanwhile, the outside of the doughnut (the crust) represents ecological boundaries beyond which earth’s natural systems are under threat. This model provides a revolutionary way to understand prosperity and set goals for humanity. According to this model, prosperity can be achieved when we are situated in the middle ring, neither overshooting planetary boundaries nor lacking the necessary social foundations for all people. As Kate Raworth, founder of Doughnut Economics, has said, “A healthy economy should be designed to thrive, not grow.”

I hope this essay helps you pause and remember the bigger picture. As you orient yourself in your role towards the larger, systemic goals we are collectively trying to achieve, take heart that you’re part of an exciting, growing community working to do the same.

Interested in learning more about the circular economy? Subscribe to the free Circularity Weekly newsletter and be sure to sign up for our April 19th Co-op Class on Zero Waste Strategies with Ben Kogan of Reusable Solutions! We’re looking forward to this empowering conversation where we’ll explore opportunities to reduce our personal impact on this planetary problem, highlighting circular systems of reuse.