Compostable Conundrum

The secret is out: Americans have a serious waste problem. Since the onset of the first publicly-funded recycling pick-up programs in the late 1960s, we’ve been trained to dutifully separate our paper, plastic, and glass from the waste stream. Billions of dollars have been spent on educational programs and infrastructure to support these initiatives and, in the decades since, we’ve packed cargo ships with countless tons of our recyclables destined for China where they’re made into goods such as shoes, bags, and new plastic products. An awareness of this cycle allowed us to feel a little less guilty about our increasingly disposable culture.

For much of the last half-century, Americans have had little incentive to consume less. It’s relatively inexpensive to buy products, and it’s even cheaper to dispose of them at the end of their short lives. We gave very little thought to where these products went after being discarded. In the summer of 2017, however, this convenient denial of our flawed relationship with consumption and waste came screeching to a halt when China announced that they were no longer interested in receiving our recyclables. Since January of 2018, China has banned imports of various types of plastic and paper and tightened contamination standards for materials it does accept. Thus, without a willing market, much of America’s carefully sorted recycling is simply ending up in the trash.

The Promise of Compostables

Amid mounting backlash against single-use plastics, many looked to the promise of compostable packaging to meet our perceived need for convenience. We were quickly sold on the notion that these products, made from renewable materials rather than petroleum, were gentler on the environment and capable of reducing waste by breaking down naturally like the banana peels in our compost heap. What we failed to realize was that many compostable products are made from chemically-intensive monocultures of genetically modified corn and that they wouldn’t actually break down on their own. Their breakdown would require high heat and moisture, conditions found mainly in special industrial facilities that don’t exist in most communities, including here in Addison County. The Addison County Solid Waste Management District (ACSWMD) is unable to accept and process compostable containers or bags. Our infrastructure hasn’t been able to keep pace with innovation and, as such, many of these products end up being burned or sent to landfills, where—deprived of oxygen and microorganisms—they don’t degrade.

They also cause serious contamination issues in recycling facilities, according to the experts at the ACSWMD. The issue of contamination causes problems for waste management facilities in both recycling and compost systems. Compostable products often look identical to their recyclable counterparts and inadvertently create more waste when mixed with recyclables on a large scale. During the processing of recyclables at solid waste facilities, compostables can degrade, contaminating the plastic, and rendering entire batches of plastic recycling too contaminated to meet market standards. Alternatively, when recyclable plastic containers find their way into the bin with compostables and are delivered to the limited number of existing high-heat composting facilities, the quality of the compost is severely compromised.

As our Co-op staff learned of these challenges, we tried to balance increasing consumer demand for more compostable packaging with the stark reality that offering these products might simply amount to greenwashing. Determined to find a solution, we continued to work with experts at the Addison County Solid Waste Management District, Casella Waste Systems, and Vermont Natural Ag Products to explore ideas. In 2018, we hatched a pilot program that involved setting up systems for collecting our compostable deli to-go containers and Casella’s agreed to transport them to Vermont Natural Ag’s compost heaps at Foster Brothers Farm where they would, ideally, turn into compost.

We knew from the onset that this was to be an experiment, as we still needed to answer some big questions: Would their processing equipment be hindered by our containers? Would the chemistry of their compost heaps handle such a significant addition of carbon? Would our staff and our customers be able to sort effectively enough to minimize contamination? In the end, the third question created the most significant hurdle to the program’s success.

Around the time that our pilot project began, a group of Middlebury College students partnered with us to collect data on the rate of contamination. They determined, through daily bouts of messy sorting and counting over the course of two weeks, that our contamination rate hovered around 30%. Upon hearing this news, we doubled-down on our efforts but, despite putting considerable energy toward sorting education and generating clear signage at the receptacles for the compostable containers, our contamination rate ultimately proved too high for the program to continue.

Where Do We Go From Here?

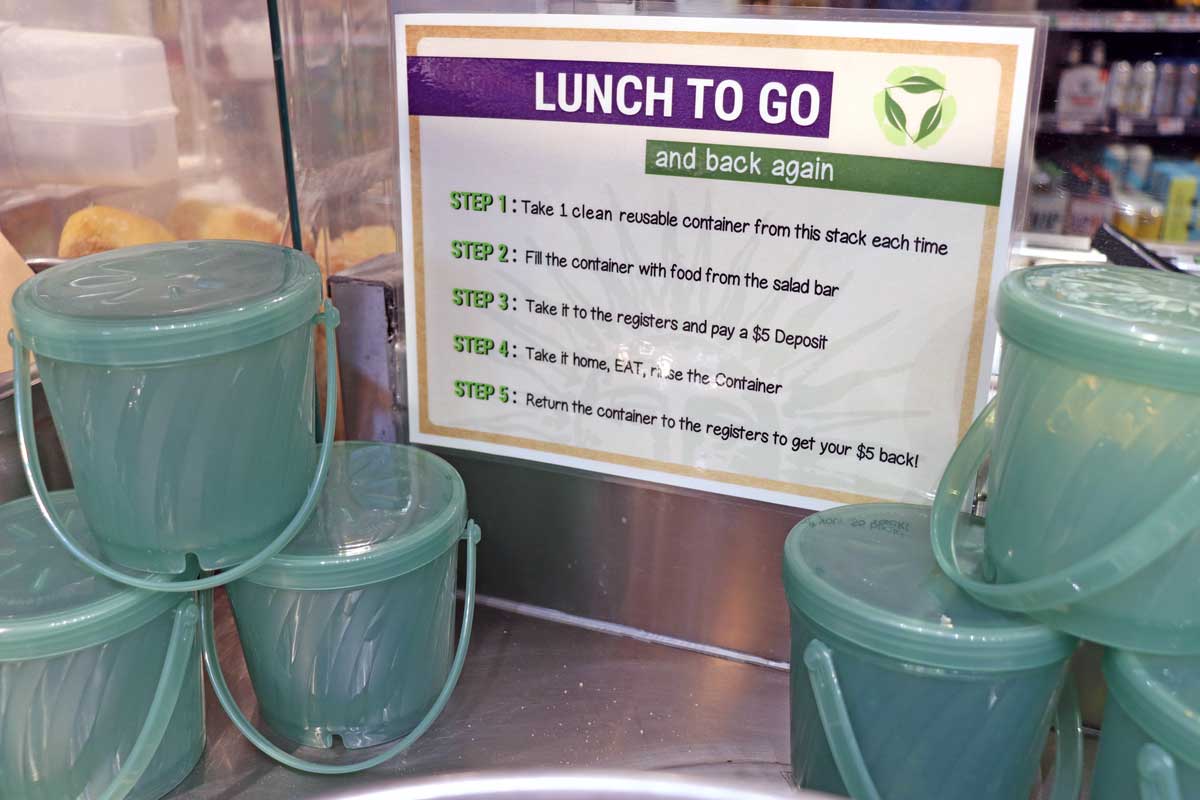

We’re still collecting clean, compostable food scraps both for pickup by area farmers and for collection by Casella’s, but we’re no longer permitted to add compostable containers to the mix. This means that all of our deli to-go containers must, unfortunately, be deposited as trash. It also means that we cannot in good conscience switch to compostable bags in our Produce Department, despite significant customer demand. Until we’re certain that these compostable bags can be received and effectively processed by our local waste management facility, it simply doesn’t make sense to use them. Thankfully, there are other options! If you’re dining in, we encourage you to choose our reusable plates and bowls. If you’re on the go, we offer a reusable to-go container that may be purchased for a $5 deposit and filled with hot bar and salad bar items. When you’re ready to return it, give it a rinse and drop it back off with any cashier to reclaim your deposit or swap it for a new, clean reusable to-go container. In order to remain compliant with State Health Department regulations, we cannot allow customers to bring their own containers for use at the hot bar or salad bar but we do encourage you to continue bringing your own containers when shopping for bulk items throughout the store.

Given that selling our recyclables to China is no longer an option and compostables don’t deliver on their promise, it’s incumbent upon us to find our own solutions. One suggestion involves the adoption of a fourth “r” beyond “reduce, reuse, and recycle”— we must learn to refuse. Becoming more discerning consumers and learning to say no to items we don’t need is an important step. Refusing disposable straws, plastic cutlery, and other single-use plastics, and saying no to compostable packaging ultimately destined for the landfill provides us with another way to vote with our hard-earned money for the kinds of changes we’d like to see in the world. When there’s no longer a market for products packaged in plastic, manufacturers will seek alternatives and we’ll all move a little closer to a zero-waste culture.

*This content first appeared as an article in the Spring 2020 edition of our Under the Sun newsletter. It has since been updated to reflect new reusable options at the Co-op.